-- -- --

A Short history of in-situ music

This text is taken from my article 'Taking part in the world: discourses on music, time and place in in-situ music' (in Liminalities, 2021). The paragrah is titled 'broad historical development of in-situ music and emerging in-situ traditions.' This paragrah gives a short, historical overview of 60 years in-situ music performances and displays the many ways in which in-situ and site-specific performances create dialogues with the concert environment.

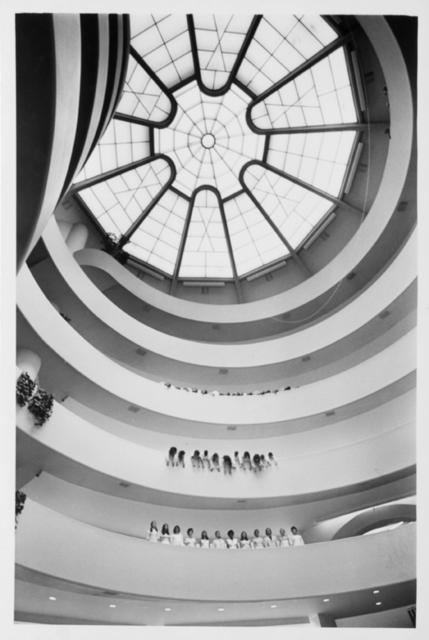

In general there have been two historical waves of in-situ music since 1950: one that preceded 1995 and one that followed. After an outburst of musical activity outside the concert hall around 1970, a two-decades period of intense activity and development followed in many locations, indoor and outdoor alike. This rich and diverse outburst was preceded by Fluxus's and Allan Kaprow's events, happenings and Cage's 4'33'' (1952) and Variations IV (1963), which opened the borders between closed, isolated, artistic halls and the surrounding environment. In 1967-68, Musica Elettronica Viva started performing in public places, abandoned factories and jailhouses. One year later Meredith Monk presented Juice: A Theatre Cantata in Three Installments for the specific, 'spiraling' architecture and surroundings of the Guggenheim Museum. Two years later she made her audience walk from an old auditorium to a disused rail depot to witness part two and three of her Vessel opera. Trevor Wishart, together with theatre-maker Michael Banks, produced an inventive sequel of music performances - called Landscape - with ice-cream cars, park music and musicians playing from a hilltop in 1970. Around 1970 the movement to leave the concert hall seemed omnipresent: Christian Wolff organized an outdoor Burdock Festival in Vermont (USA) in which several of his Prose Pieces (such as Groundspace) were premiered and Karlheinz Stockhausen situated five groups of performers in a Berlin park in Sternklang (1971). Two years later, David Dunn brought performers to deserts and other natural locations, triggering sound reactions from specific animals.

Singers in Meredith Monk's Juice (1969) performance, made for the Guggenheim Museum.

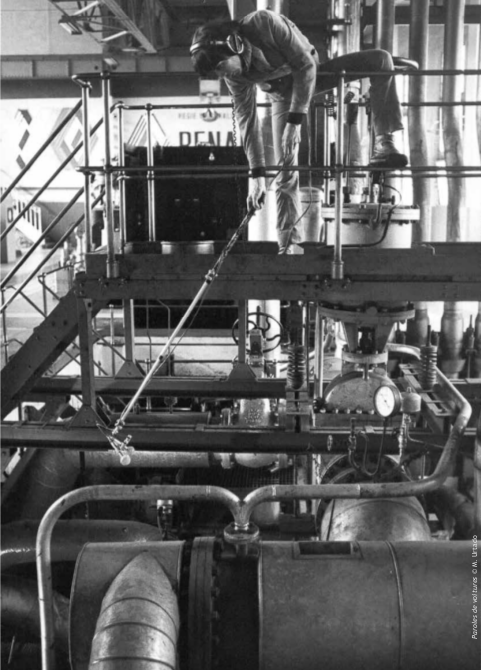

There are four musicians that started their in-situ practice during this vivid outburst in the 1970s, remained active during the decline of in-situ music in the 90s, continued working in the 21st century and have built up an extensive, influential oeuvre of in-situ compositions. The first one is Alvin Curran , who integrated local, cultural diversities and large numbers of performers in his cycle of Riti Marittimi and other compositions. The second, Nicolas Frize, preferred large-scale productions in urban, work-related settings such as car factories, train stations or libraries. Since her Sonic Meditations (1974) Pauline Oliveros, the third musician, extended (musical) performance to encompass a variety of listening modes and an embodied awareness of oneself, the other participants and the (performance) environment. The fourth, Raymond Murray Schafer, brought audiences and performers to natural locations in his music-theatre cycle Patria to re-enact and revive a mythical connection between humans, animals, plants and the earth.

Nicolas Frize collecting sounds for Paroles de voitures (1984)

Composers such as Alvin Lucier, Wishart and Dunn who - in different ways - had been very active in composing and setting up performances outside concert halls between 1965 and 1985, retreated to concert halls, studios and research institutes in the 1990s or traded in-situ performances for sound installations or field recordings. The 1990s were also a transition period between emerging and 'disappearing' in-situ musicians. Four composers started making in-situ productions in the 1980s, helped to bridge the 1990s and created continuity between the two historical in-situ waves. These are Llorenç Barber (based in Spain), Godfried-Willem Raes (in Belgium) and the French composers Michel Risse and Pierre Sauvageot

From the second half of the 1990s onwards, new in-situ music emerged (the second in-situ 'wave') and in the past twenty years there has been a small but steady international growth of in-situ music. Ecological concerns and a preference for outdoor, natural performance sites are recognizable in the work of Erik Griswold, Robert Morris and John Luther Adams. Other musicians (Lisa Bielawa, Merlijn Twaalfhoven, Tomoko Momiyama, Stephen Montague and Makoto Nomura) stress the social process, community-related or political meaning of a concert, its location and preparation. Building upon the work of Cage and Oliveros, and focussing on (performative) listening and relational aspects of a performance, Ablinger, Robert Blatt, Carolyn Chen, David Helbich, Marc Glenn Jensen, Suzanne Thorpe and Manfred Werder have added numerous in-situ works since 1995. Finally, there are the previously mentioned improvisation ensembles and in-situ musicians that are hard to categorize, such as Kathy Kennedy, Kesten, Daniel Ott, Kirsten Reese and Stephen Chase, the latter creating a mix of sound walks and performances in his Out-of-doors suite (2011-present).

Oorkest performance van de Waterlanders

During 60 years of in-situ performances, new and existing in-situ traditions have emerged and developed. First, the old practice of street music (marches, demonstrations, busking, playing automatic barrel organs and creating a short, attention-grabbing act) was mixed with experimental instrument building, sound installations and (portable) electro-acoustic music, resulting in parades of performers with eye- and ear-catching instruments in the works of Sauvageot, Risse, Raes and compagnies such as Décor Sonore. Second, a tradition of 'city concerts' emerged, with origins reaching back to the Symphony of factory sirens (1922) by Arseny Avraamov. A large area (such as a city, town or neighbourhood) was turned into one concert hall and made to resound by using machines and loud instruments (church bells, ship horns, sirens, etc.), often involving large numbers of (local) performers. A large part of the in-situ oeuvre of Curran and Barber illustrate this emerging tradition. The third and fourth in-situ traditions are the previously described relational performances (mainly building on Oliveros's practice) and in-situ performances in natural locations. The latter consists of two overlapping, but not identical, practices: one (in the footsteps of Schafer) focussing on the natural parts of a site and a holistic concept of nature and another (building on Dunn) aiming at interaction with animals (for example, the performances of David Rothenberg)

The next two traditions are harder to localize as their influence is more pervasive and diffused.

The fifth one comprises Fluxus events and happenings in the 1960s; the desire to fuse daily life and art and rely on games, concepts and imagination, left an enduring influence on elements of in-situ music. The last tradition consists of (educational) sound games and exercises (of Hugh Davies, Schafer, Oliveros, Wishart, etc.), which not only focus on listening but also on producing sound. In each collection of games and exercises there are examples of interaction with the surroundings. Because of their educational background and accessibility, these games have been performed in a variety of (educational and other) situations and locations.